Eboracum’s People

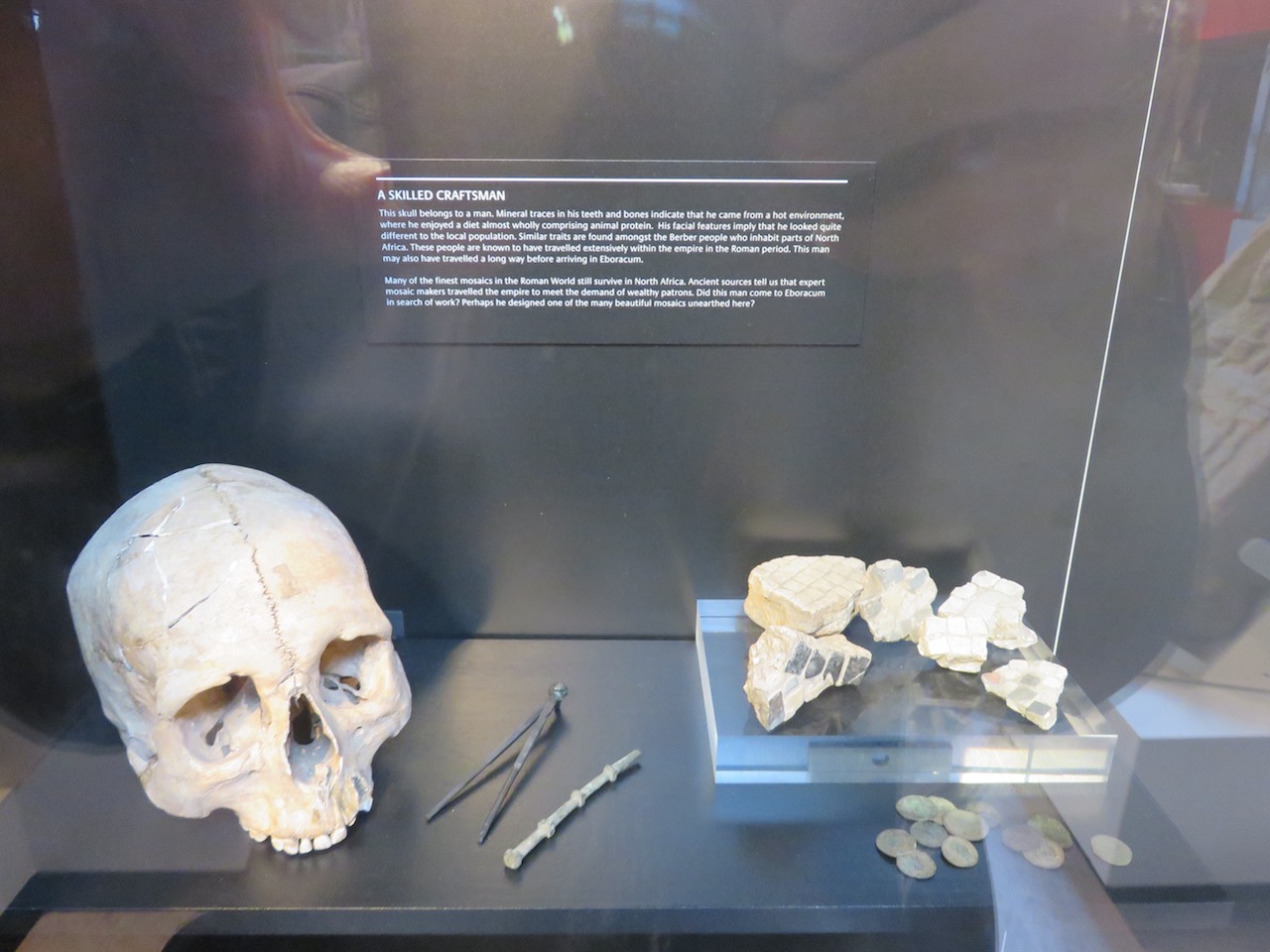

On my recent visit to York, it was the stories of Eboracum’s people that captured my imagination. The Yorkshire Museum does a great job showcasing the people of Roman York. The exhibit includes their backgrounds which they have discovered by examining the remains from the Roman graveyard. They studied the grave goods, as well as the bones, teeth, and skulls to find clues of where the people came from, their ages, and their occupations.

One man came from North Africa, where many expert mosaic makers came from. He may have travelled from one end of the empire to the other creating mosaics for the wealthy. Another was a local man who was between 35 and 50 when he died. They could tell he suffered from a bad back because of his spine and shoulders. Another was only in his twenties when he died, but the minerals in his teeth and bones showed he ate a lot of fish and came from a cold climate, possibly the Baltic region.

I also met Eboracum’s people through their inscribed grave markers. Julia Velva was around 50 when she died. Her heir, Aurelius Mercurialis, and his family are portrayed gathering at her tombstone. On another tombstone there is a depiction of Aleia Aeliana, reclining on a couch beside her husband who had his arms around her. The tombstone of Flavia Augustina, who died along with her two infant children, was erected by her husband Caeresius Augustinus, an ex-soldier.

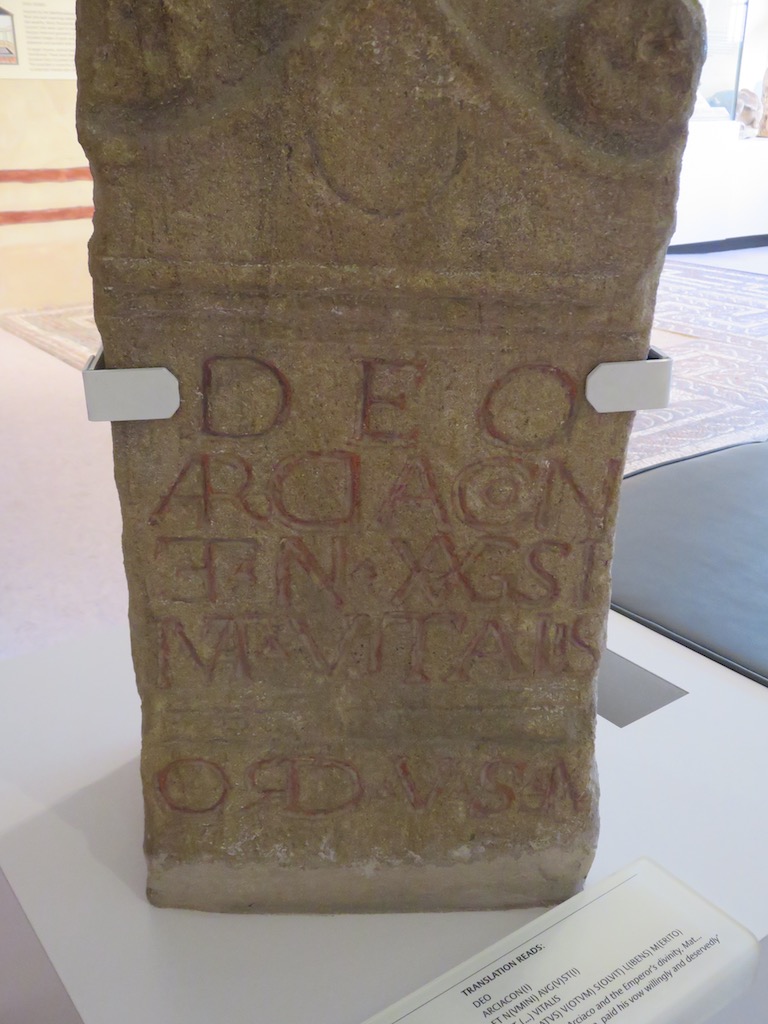

Soldiers from the fort at Eboracum also left their mark while they were alive. A centurion, Mat(…) Vitalis, dedicated an altar to his god Arciaco and the divine emperor.

Several well-known and historically important people were connected to Eboracum as well. The Emperor Septimius Severus died in Eboracum in AD 211 after coming to Britannia to try to conquer the north of the island. The most notable, though, was Constantine the Great, who was made emperor here in AD 306 after the death of his father, Constantius.

I also found footprints of Romans and their pets beneath the Yorkminster, in the display of the remains of Eboracum’s fort. The hobnail footprints of a soldier and the paw prints of a dog were captured in the dried clay of Roman bricks.

For more information about York’s Roman past, see Eboracum Quick Facts and Yorkshire Museum Quick Facts.